The 1938 Sandwich Forest Fire

- Joan Osgood

- Feb 19, 2021

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 7, 2025

I’d first heard the story of the 1938 forest fire as a young girl from my father, when I asked him about the large boulder at the top of the hill on Route 130.

And I can remember exactly when I asked him. It was back about 65 years ago. He used to take the four of us—my sister Barbara, my brothers Bill and Pete, and me—on jaunts through the backwoods of Forestdale and South Sandwich just as dusk was setting in.

We’d ride in his creaky but reliable grocery delivery truck. It had a large searchlight attached to the driver’s windshield that you could maneuver from a handle inside. He’d shine it into the wooded fields, and in those days there were many fields but no houses, just dirt roads and woods. He’d shine the spotlight so we could see deer grazing in the fields. They would look up and their eyes would glow in the light and I thought them the most elegant creatures. Still do.

Anyway, as we topped the hill just south of where Exit 2 is today, I asked him about the boulder, and he said it was for three men who lost their lives fighting a forest fire. I never forgot that, and of course since that time I have read various articles about it over the years.

What I had never heard or read about, though, was the reaction in the aftermath of the deadly fire as reported in a 1938 article in the Chatham Monitor and other newspapers of the day.

People were outraged. Not only residents of our town, but people from towns all across the Cape. They were incensed about the military reservation’s part in this deadly, awful fire. And they lost no time in seeking a reckoning from the military and the state of Massachusetts.

Selectman George A. Mooney conducted a meeting on May 6, 1938, just a few short days after the fire, which the Monitor likened to a “public inquest.” In addition to citizens from across the Cape, there were town officials, forest wardens, and fire and police chiefs also in attendance. The stated purpose of this gathering was to come to agreement as to who to hold responsible for the fire that left three men dead and 3,000 to 4,000 acres of scorched woodland.

From the reports of the day there seemed to be no doubt as to the cause of the fire. It started on the military reservation and spread to Shawme State Forest (in 1938 to be renamed Shawme-Crowell State Forest). The chiefs of police in Sandwich and Bourne, Thomas Kelleher and William Crump, both verified this.

Adjutant General Charles H. Cole of the National Guard also attended Selectman Mooney’s meeting and confirmed this fact. He placed the blame on a group of 25 Works Progress Administration workers who were clearing a section of the reservation by burning brush.

They were having lunch when a fire broke out from the embers of the brush they had been clearing. While trying to extinguish this, another fire broke out and they were not able to get it under control as it swept quickly toward Sandwich. Adjutant General Cole stated, “Instructions which were given WPA workers regarding brush burning evidently were not carried out.”

On May 1, 1938, Shawme State Forest was renamed Shawme-Crowell State Forest in honor of Lincoln Crowell, who conceived and worked tirelessly to secure land from the state to establish this forest. He was a leader known widely not only on Cape Cod but throughout New England in reforestation, forest fire prevention, and firefighting work. Interestingly, he was tragically killed in a car and train accident in Brewster on April 4, 1938, just 25 days prior to the fire in the forest that would come to bear his name. (In 1916 his brother, David, established Crow Farm in Sandwich, which is still thriving under his great-nephew, Paul Crowell.)

It was a horrible fire. Five men were trapped near a fire break in the Shawme-Crowell State Forest: Deputy Chief Clarence Gibbs of the Buzzards Bay Fire Department; Henry A. Jarvis of Sagamore; Ervin A. Draber of Buzzards Bay; and Thomas E. Adams and Gordon King, both of Sandwich.

Using the standard firefighting method, they set a backfire in a section of the forest. But suddenly, with high winds, the main fire encircled them with flames. All except Gordon King dropped to the ground as flames swept over them and somehow, though badly burned, they were able to crawl out.

King tried to outrun the fire but was overcome. All five were sped to Cape Cod Hospital. Tragically, Thomas Adams died on April 28 and Gordon King on April 30. It was thought initially that Mr. Draber might survive, but he succumbed to his burns on June 18 in the Boston hospital where he had been transferred.

All three men left behind widows and very young children. Clarence Gibbs and Henry A. Jarvis both survived their injuries.

In a conversation I recently had with Mr. Jerry Ellis—a Bourne native, historian, and former selectman—he had a couple key memories of the fire:

I was about five years old, but I remember the fire clearly to this day. My father picked

me up in Sagamore and said, "I want to show you something." He drove over the

Sagamore Bridge around the rotary and drove back over the bridge. As we approached

the top of the bridge all you could see was smoke and fire coming from the military base.

I knew Henry Jarvis growing up and I was good friends with his son, Buddy. We went

clamming every Saturday. I remember Mr. Jarvis—his ears were burned terribly from

the fire. He told me that he and Clarence Gibbs ran and climbed under a fire engine

and he always said that was what saved him and Clarence from being killed in the fire.

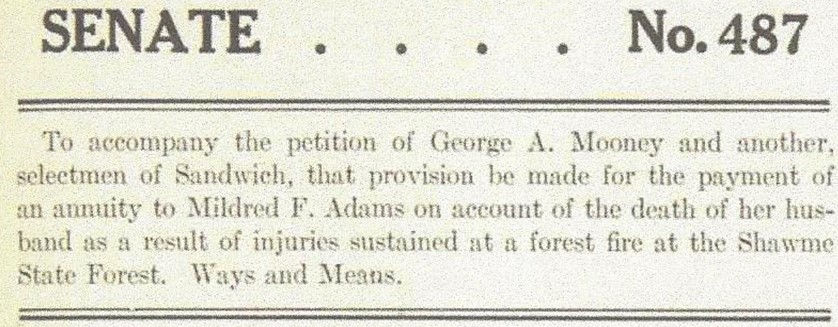

Petitions were circulated all across the Cape asking the Massachusetts Legislature to reimburse the victims' families for medical costs and to pay them annuities in the amount of $4,200 each. Sandwich also sought reimbursement for its firefighting expenses.

I found the following language in the legislative bills that paid money to the widows: “…[for the] purpose of discharging a moral obligation of the Commonwealth….” It offered perhaps some acknowledgment that these heroic men died fighting a fire on state-owned land.

At the same time the petitions were being circulated, the Cape Cod Foresters Association was already planning a memorial for the three men who lost their lives. It was to be erected in a section of Shawme State Forest on Route 130. Contributions were sought from the citizens of Barnstable County and school children across the Cape were donating their pennies.

Exactly a year from the date of this awful fire, on April 27, 1939, a memorial ceremony was held. A granite boulder with a bronze plaque was dedicated. A. Lincoln Estes, the state's deputy forest warden, led the ceremony.

In his closing remarks he avowed that, “Fire…can and does take from our homes and firesides devoted husbands and loving fathers and leaves at family hearthstones a vacant chair which can never be refilled.”

The death of Gordon King was not the end of the tragedies to befall that family. In the winter of 1942 Gordon and Grace King’s son, eight-year-old Robert of Forestdale, was lost in drifting snow and high wind. Hundreds of people searched for him—citizens, state police, soldiers from Camp Edwards, and even the Boy Scouts. He was found unconscious a day later and died in an ambulance on the way to the base hospital.

Joan Osgood is a member of the Friends of the Sandwich Town Archives, a dedicated, all-volunteer, 501(c)(3) nonprofit committed to supporting and promoting the archives’ collections and the rich, diverse history of the town of Sandwich.

Comments