Who Burned Down the Freeman Farm? (Part 3)

- Kaethe Maguire

- Aug 12, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 7, 2025

The list of Sandwich residents who tried hard to save the remaining farm--the home and unique double barn--are many. I would like to recognize some of these preservation-minded people. Some have passed on, but some are still living.

First and foremost is Russell Lovell, Sandwich town historian. Lovell wrote letter after letter to authorities and reached out to Freeman family members in an effort to save the home. Senator Paul Tsongas was also involved in trying to save the structures.

Paul White, then a member of the Sandwich Historic District Committee, and David Allen, formerly of East Sandwich, tried to buy the structures and have them moved. They were met with obstacle after obstacle in this quest.

Lovell also tried to have the home listed on the National Register of Historic Places but was rebuffed. Canal Electric, now owning the 11 acres on which the home and barn stood, was against that, of course. And the infamous James Watts, then Secretary of the Interior, dismantled the Heritage Conservation and Recreational Services, which included the Register of National Places and administered the National Preservation Act of 1966. Thankfully, this was reversed by President Carter.

Paul White was eventually able to buy the barn and won the approval of the Sandwich Historic District Committee to move it. It rests today at 8 River Street, abutting the marsh in the yard of then owner Ruth Kelly. The barn is long and unusual and is actually two barns joined together. The barn is balloon framing whereas the home was post and beam construction.

Also showing great effort was George Sutton, who wore many hats in Sandwich including serving on the Sandwich Historic District Committee. Sutton wanted to create a Friends of the Freeman Farm nonprofit trust. Bourne had led by example in 1979 by preserving the endangered and now restored Briggs House, now called the Briggs McDermott House and home of the Historical Society of Bourne. Sutton also enlisted Senator Edward Kennedy’s help.

Barbara Gill, who became our next archivist following Russell Lovell in 1988, and a member of the Sandwich Historical Commission, typed letter after letter to officials.

Nancy Titcomb of Titcomb’s Book Store, who had saved the Deacon Eldred house and founded the Thornton Burgess Society, was also involved.

Architect Milton Swartz and auction house co-owner Janet Johnson also worked with the town. Johnson offered $15,000 to begin a nonprofit organization to be centered at the home.

Richard Connor, then head of the Sandwich Library, and some of the library trustees, offered a portion of the library's land for the buildings. This was a grass roots attempt by many key Sandwich citizens who cared about their history.

By 1979 the home had been vandalized and robbed twice. Not only furniture but windows, old woodwork, doors, and piles of documents kept for years and years by the family were taken. Obviously, this was the work of professionals.

Knowing that Canal Electric really had no interest in the house and barn, White and Allen went before the Historic District Committee to request that they move the historic structures. That was denied on October 28, 1980 and again on December 2, 1980. The rather short-sighted excuse was that they didn’t want the structures removed from their original setting. White countered that the coal conveyor shoot would be 40 feet away from the home!

Canal Electric admitted they had bought the 11.5 acres for the purpose of bringing coal to the power plant. If ever there was a messy conundrum, this was it. Jonathan Leonard, from an old Sandwich family, said that essentially Canal Electric was forcing the structures off the site, but in turn they were denied the right to move them.

Talk about being between a rock and a hard place! Leonard wanted, like so many others, to move the buildings in order to save them.

Efforts went on for years. But very little if any support came from elected Sandwich officials. Milton Smith, Vice President of Canal Electric and a Sandwich resident, also refused all offers to move the structures. And of course, as already noted, the Historic District Committee didn’t want the structures moved. Canal Electric wanted to surround the buildings with a chain link fence, which surely would have been refused by the Historic District Committee.

Sadly, most of the scattered descendants did not show interest. The Freemans did not have a family association like the Nye's very active association. But there were exceptions to the lack of family involvement.

Warren Gray Freeman, who was not directly connected to the family, but was a resident of East Sandwich, did a writing campaign to try to save the farm buildings. He wrote repeatedly to the select board and received no answers. Warren’s Freeman descendants came over from England in the 1700’s and settled in Maine. As luck would have it, his grandfather was for years the caretaker of the Freeman Farm during the time the Clarks and Carpenters used it as a summer residence. So Warren had spent summers on the farm with his grandfather. The house had no electricity and no central heat, but Warren had only happy memories of spending summers there.

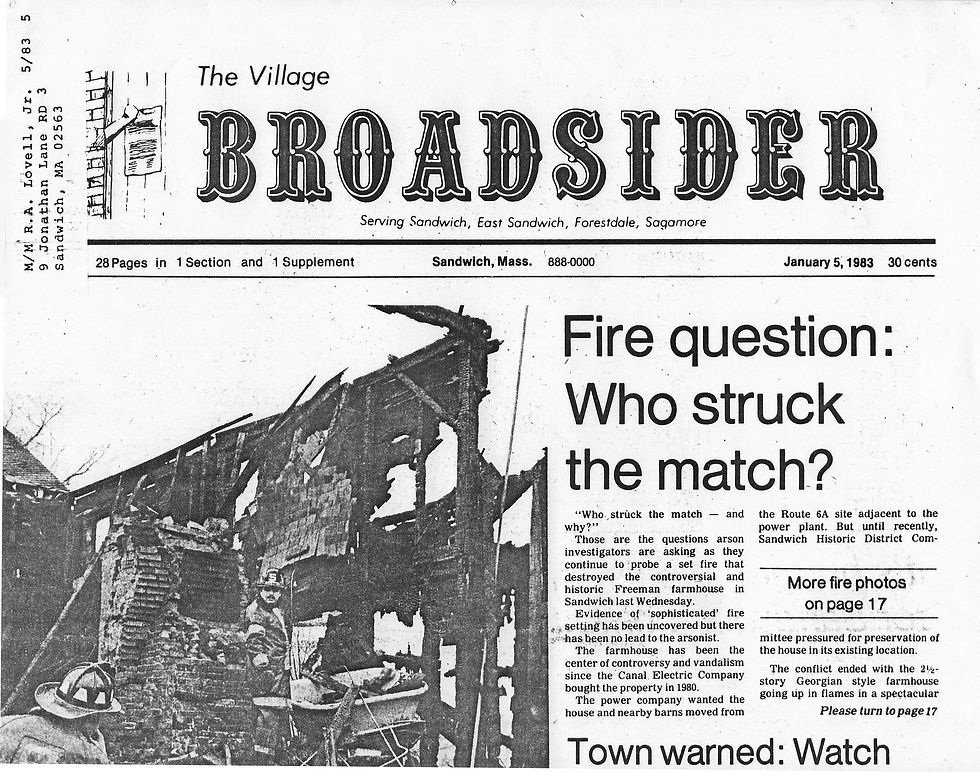

So you decide. Who do you think set the arson fire that destroyed the Freeman family home?

While the town lost such a valuable historical asset due to arson, it will remain a mystery with many theories as to who or why the Freeman Farm home was destroyed.

What’s your theory?

This is the third of a three-part series.

Kaethe Maguire is a member of the Friends of the Sandwich Town Archives, a dedicated, all-volunteer, 501(c)(3) nonprofit committed to supporting and promoting the archives’ collections and the rich, diverse history of the town of Sandwich.

Comments